Science Behind M@H

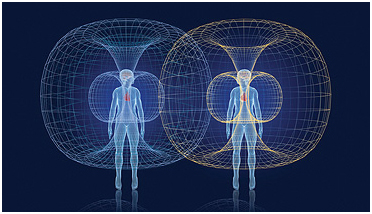

Your heart emits an electromagnetic field that changes according to your emotions.

Others can pick up the quality of your emotions through the electromagnetic energy radiating from your heart. (From HeartMath Institute)

By learning self-regulation techniques that allow us to shift our physiology into a more coherent state, the increased physiological efficiency and alignment of the mental and emotional systems accumulates resilience (energy) across all four energetic domains.

Having a high level of resilience is important not only for bouncing back from challenging situations, but also for preventing unnecessary stress reactions (frustration, impatience, anxiety), which often lead to further energy and time waste and deplete our physical and psychological resources.

Most people would agree it is the ability to adjust and self-regulate one’s responses and behavior that is most important in building and maintaining supportive, loving relationships and effectively meeting life’s demands with composure, consistency and integrity.

Findings from the HeartMath Institute

Heart Intelligence, the Unifying Factor |

Heart-Brain Interactions

What do researchers mean when they talk about heart-brain interactions?

Researchers with the HeartMath Institute and other entities have shown that the human heart, in addition to its other functions, actually possesses the equivalent of its own brain, what they call the heart brain, which interacts and communicates with the head brain.

Traditionally, scientists believed, it was the brain that sent information and issued commands to the body, including the heart, but we now know the reverse is true as well.

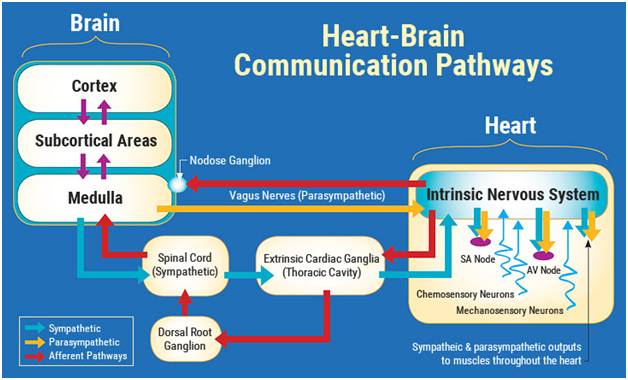

“Research has shown that the heart communicates to the brain in four major ways: neurologically (through the transmission of nerve impulses), biochemically (via hormones and neurotransmitters), biophysically (through pressure waves) and energetically (through electromagnetic field interactions),” HMI researchers explain in Science of the Heart, an overview of research conducted by the institute.

The heart is, in fact, a highly complex, self-organized information processing center with its own functional “brain” that communicates with and influences the cranial brain via the nervous system, hormonal system and other pathways. These influences profoundly affect brain function and most of the body’s major organs, and ultimately determine the quality of life.

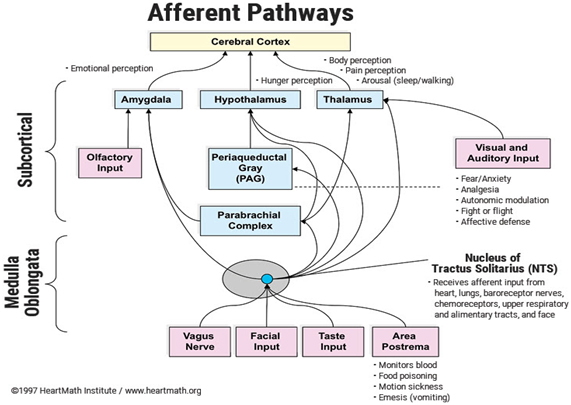

Diagram of the currently known afferent pathways by which information from the heart and cardiovascular system modulates brain activity. Note the direct connections from the NTS to the amygdala, hypothalamus and thalamus. Although not shown, there also is evidence emerging that there is a pathway from the dorsal vagal complex that travels directly to the frontal cortex.

The neural communication pathways interacting between the heart and brain are responsible for the generation of HRV. The intrinsic cardiac nervous system integrates information from the extrinsic nervous system and the sensory neurites within the heart. The extrinsic cardiac ganglia located in the thoracic cavity have connections to the lungs and esophagus and are indirectly connected via the spinal cord to many other organs, including the skin and arteries. The vagus nerve (parasympathetic) primarily consists of afferent (flowing to the brain) fibers that connect to the medulla. The sympathetic afferent nerves first connect to the extrinsic cardiac ganglia (also a processing center), then to the dorsal root ganglion and the spinal cord. Once afferent signals reach the medulla, they travel to the subcortical areas (thalamus, amygdala, etc.) and then the higher cortical areas.

The Heart as a Hormonal Gland

In addition to its extensive neurological interactions, the heart also communicates with the brain and body biochemically by way of the hormones it produces. Although not typically thought of as an endocrine gland, the heart actually manufactures and secretes a number of hormones and neurotransmitters that have a wide-ranging impact on the body as a whole.

The heart was reclassified as part of the hormonal system in 1983, when a new hormone produced and secreted by the atria of the heart was discovered. This hormone has been called by several different names – atrial natriuretic factor (ANF), atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and atrial peptide. Nicknamed the balance hormone, it plays an important role in fluid and electrolyte balance and helps regulate the blood vessels, kidneys, adrenal glands and many regulatory centers in the brain.

Increased atrial peptide inhibits the release of stress hormones,[19] reduces sympathetic outflow] and appears to interact with the immune system.]

Even more intriguing, experiments suggest atrial peptide can influence motivation and behavior

Heart cells and norepinephrine, epinephrine,dopamine and oxytocin

It was later discovered the heart contains cells that synthesize and release catecholamines (norepinephrine, epinephrine and dopamine), which are neurotransmitters once thought to be produced only by neurons in the brain and ganglia.]

More recently, it was discovered the heart also manufactures and secretes oxytocin, which can act as a neurotransmitter and commonly is referred to as the love or social bonding hormone.

Beyond its well-known functions in childbirth and lactation, oxytocin also has been shown to be involved in cognition, tolerance, trust and friendship and the establishment of enduring pair-bonds. Remarkably, concentrations of oxytocin produced in the heart are in the same range as those produced in the brain

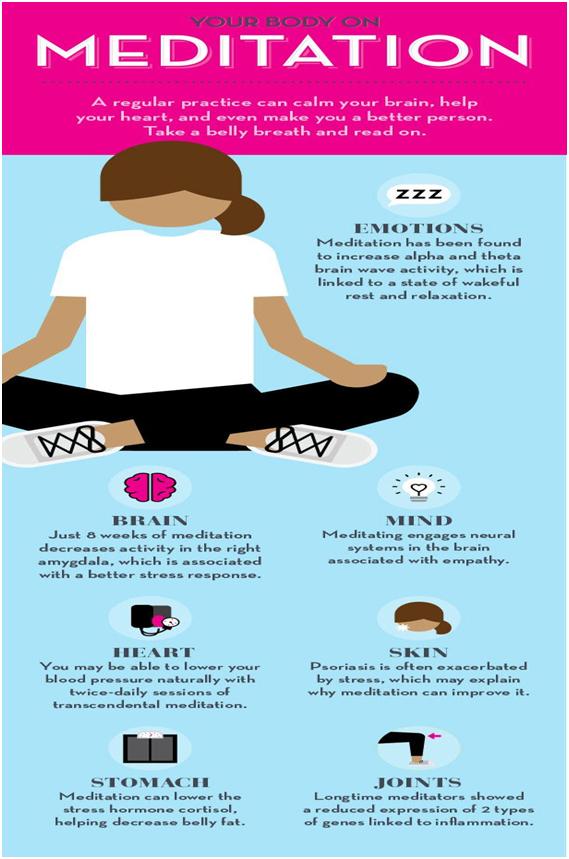

Stephanie Eckelkamp Ilustration by Tantika TivoraJune,27,2014 Sources: Frontiers in Human Neuroscience; Alternative and Complementary Medicine; Psychological Science; American Heart Association; Health Psychology; British journal of Dermatology; Psychoneuroendocrinology Journal of Dermatology; Psychoneuroendocrinology

The Mysteries of the Heart

Research explains how the physical and energetic heart plays an extraordinary role in our lives!

Our heart rhythms affect the brain’s ability to process information. The heart has 40,000 sensory neurons involved in relaying ascending information to the brain.

The human heart’s magnetic field can be measured several feet away from the body.

Negative emotions can create nervous system chaos, but positive emotions do the opposite.

Positive emotions can increase the brain’s ability to make good decisions.

You can boost your immune system by focusing on positive emotions.

A mother’s brainwaves can synchronize to her baby’s heartbeats even when they are a few feet apart.

Positive emotions create physiological benefits in your body.

In fetal development, the heart forms and starts beating before the brain begins to develop.

Did you know the heart has a brain of its own?

Dr. J. Andrew Armour introduced the term, “heart brain,” in 1991. Armour showed that the heart’s complex nervous system qualified it as a “little brain.”

Intrinsic Cardiac Afferent Neurons

The heart brain, like the brain proper, has an intricate network of neurons, neurotransmitters, proteins and support cells. It can act independently of the cranial brain and has extensive sensory capacities.

Scientists at the HeartMath Institute have conducted research on emotional energetics, coherence, heart-brain connection, heart intelligence and practical intuition.

Heart-Brain Factoids

Resilience, Stress and Emotions

As far back as the middle of the last century, it was recognized that the heart, overtaxed by constant emotional influences or excessive physical effort and thus deprived of its appropriate rest, suffers disorders of function and becomes vulnerable to disease

An early editorial on the relationships between stress and the heart accepted the proposition that in about half of patients, strong emotional upsets precipitated heart failure.

Unspecified negative emotional arousal, often described as stress, distress or upset, has been associated with a variety of pathological conditions, including hypertension] silent myocardial ischemia] sudden cardiac death, coronary disease,cardiac arrhythmia, sleep disorders, metabolic syndrome,diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, fatigue, and many other disorders.

Stress and negative emotions have been shown to increase disease severity and worsen prognosis for individuals suffering from a number of different pathologies.

On the other hand, positive emotions and effective emotion self-regulation skills have been shown to prolong health and significantly reduce premature mortality.

From a psychophysiological perspective, emotions are central to the experience of stress. It is the feelings of anxiety, irritation, frustration, lack of control, and hopelessness that are actually what we experience when we describe ourselves as stressed. Whether it’s a minor inconvenience or a major life change, situations are experienced as stressful to the extent that they trigger emotions such as annoyance, irritation, anxiety and overwhelm.

In essence, stress is emotional unease, the experience of which ranges from low-grade feelings of emotional unrest to intense inner turmoil. Stressful emotions clearly can arise in response to external challenges or events, and also from ongoing internal dialogs and attitudes.

Recurring feelings of worry, anxiety, anger, judgment, resentment, impatience, overwhelm and self-doubt often consume a large part of our energy and dull our day-to-day life experiences.

Additionally, emotions, much more so than thoughts alone, activate the physiological changes comprising the stress response.

Our research shows a purely mental activity such as cognitively recalling a past situation that provoked anger does not produce nearly as profound an effect on physiological processes as actually engaging the emotion associated with that memory. In other words, reexperiencing the feeling of anger provoked by the memory has a greater effect than thinking about it

Resilience and Emotion Self-Regulation

Our emotions infuse life with a rich texture and transform our conscious experience into a meaningful living experience. Emotions determine what we care about and what motivates us. They connect us to others and give us the courage to do what needs to be done, to appreciate our successes, to protect and support the people we love and have compassion and kindness for those who are in need of our help. Emotions are also what allow us to experience the pain and grief of loss. Without emotions, life would lack meaning and purpose.

Emotions and resilience are closely related because emotions are the primary drivers of many key physiological processes involved in energy regulation. We define resilience as the capacity to prepare for, recover from and adapt in the face of stress, adversity, trauma or challenge. Therefore, it follows that a key to sustaining good health, optimal function and resilience is the ability to manage one’s emotions.

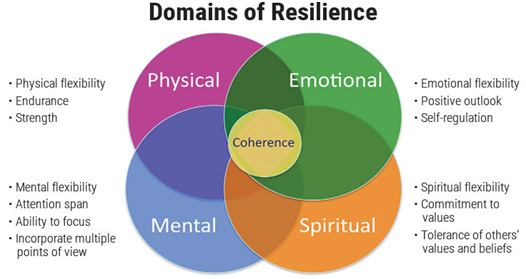

It has been suggested that resilience should be considered as a state rather than a trait and that a person’s resilience can vary over time as demands, circumstances and level of maturity change. We suggest that the ability to build and sustain resilience is related to self-management and efficient utilization of energy resources across four domains: physical, emotional, mental and spiritual (Figure 2.1).

Physical resilience is basically reflected in physical flexibility, endurance and strength, while emotional resilience is reflected in the ability to self-regulate, degree of emotional flexibility, positive outlook and supportive relationships. Mental resilience is reflected in the ability to sustain focus and attention, mental flexibility and the capacity for integrating multiple points of view. Spiritual resilience is typically associated with commitment to core values, intuition and tolerance of others’ values and beliefs.

Figure 2.1 Domains of Resilience.

Having a high level of resilience is important not only for bouncing back from challenging situations, but also for preventing unnecessary stress reactions (frustration, impatience, anxiety), which often lead to further energy and time waste and deplete our physical and psychological resources. Most people would agree it is the ability to adjust and self-regulate one’s responses and behavior that is most important in building and maintaining supportive, loving relationships and effectively meeting life’s demands with composure, consistency and integrity.

If people’s capacity for intelligent, self-directed regulation is strong enough, then regardless of inclinations, past experiences or personality traits, they usually can do the adaptive or right thing in most situations

It is our experience that the degree of alignment between the mind and emotions can vary considerably. When they are out of sync, it can result in radical behavior changes that cause us to feel like there are two different people inside the same body.

It can also result in confusion, difficulty in making decisions, anxiety and a lack of alignment with our deeper core values. Conversely, when the mind and emotions are in sync, we are more self-secure and aligned with our deeper core values and respond to stressful situations with increased resilience and inner balance.

Our research indicates that the key to the successful integration of the mind and emotions lies in increasing one’s emotional self-awareness and the coherence of, or harmonious function and interaction among, the neural systems that underlie cognitive and emotional experience.

An important aspect of understanding how to increase self-regulatory capacity and the balance between the cognitive and emotional systems is the inclusion of the heart’s ascending neuronal inputs on subcortical (emotional) and cortical (cognitive) structures which, as discussed above, can have significant influences on cognitive resources and emotions. Information is conveyed in the patterns of the heart’s rhythms (HRV), that reflects current emotional states.

The patterns of afferent neural input (coherence and incoherence) to the brain affect emotional experience and modulate cortical function and self-regulatory capacity. We have found that intentional activation of positive emotions plays an important role in increasing cardiac coherence and thus self-regulatory capacity.[5] These findings expand on a large body of research into the ways positive emotional states can benefit physical, mental and emotional health.[44-49]

Because emotions exert such a powerful influence on cognitive activity, intervening at the emotional level is often the most efficient way to initiate change in mental patterns and processes. Greater alignment is associated with improved decision- making, creativity, listening ability, reaction times and coordination and mental clarity

Coherence

Definitions of Coherence

Many contemporary scientists believe it is the underlying state of our physiological processes that determines the quality and stability of the feelings and emotions we experience.

The feelings we label as positive actually reflect body states that are coherent, meaning “the regulation of life processes becomes efficient, or even optimal, free-flowing and easy] and the feelings we label as “negative,” such as anger, anxiety and frustration are examples of incoherent states.

It is important to note, however, these associations are not merely metaphorical. For the brain and nervous system to function optimally, the neural activity, which encodes and distributes information, must be stable and function in a coordinated and balanced manner. The various centers within the brain also must be able to dynamically synchronize their activity in order for information to be smoothly processed and perceived. Thus, the concept of coherence is vitally important for understanding optimal function.

The various concepts and measurements embraced under the term coherence have become central to fields as diverse as quantum physics, cosmology, physiology and brain and consciousness research.

Coherence has several related definitions, all of which are applicable to the study of human physiology, social interactions and global affairs.

The most common dictionary definition is the quality of being logically integrated, consistent and intelligible, as in a coherent statement.[159]

A related meaning is the logical, orderly and aesthetically consistent relationship among parts.

Coherence always implies correlations, connectedness, consistency and efficient energy utilization. Thus, coherence refers to wholeness and global order, where the whole is greater than the sum of its individual parts.

In physics, coherence also is used to describe the coupling and degree of synchronization between different oscillating systems. In some cases, when two or more oscillatory systems operate at the same basic frequency, they can become either phase- or frequency-locked, as occurs between the photons in a laser.] This type of coherence is called cross-coherence and is the type of coherence that most scientists think of when they use the term.

In physiology, cross-coherence occurs when two or more of the body’s oscillatory systems, such as respiration and heart rhythms, become entrained and operate at the same frequency.

Another aspect of coherence relates to the dynamic rhythms produced by a single oscillatory system. The term autocoherence describes coherent activity within a single system. An ideal example is a system that exhibits sine-wavelike oscillations; the more stable the frequency, amplitude and shape, the higher the degree of coherence. When coherence is increased in a system that is coupled to other systems, it can pull the other systems into increased synchronization and more efficient function.

The coherent state has been correlated with a general sense of well-being and improvements in cognitive, social and physical performance. We have observed this association between emotions and heart-rhythm patterns in studies conducted in both laboratory and natural settings and for both spontaneous and intentionally generated emotions.

The Coherence Model Postulates:

- The functional status of the underlying psychophysiological system determines the range of one’s ability to adapt to challenges, self-regulate and engage in harmonious social relationships. Healthy physiological variability, feedback systems and inhibition are key elements of the complex system for maintaining stability and capacity to appropriately respond to and adapt to changing environments and social demands.

- The oscillatory activity in the heart’s rhythms reflects the status of a network of flexible relationships among dynamic interconnected neural structures in the central and autonomic nervous systems.

- State-specific emotions are reflected in the patterns of the heart’s rhythms independent of changes in the amount of heart rate variability.

- Subcortical structures constantly compare information from internal and external sensory systems via a match/mismatch process that evaluates current inputs against past experience to appraise the environment for risk or comfort and safety.

- Physiological or cardiac coherence is reflected in a more ordered sine-wavelike heart-rhythm pattern associated with increased vagally mediated HRV, entrainment between respiration, blood pressure and heart rhythms and increased synchronization between various rhythms in the EEG and cardiac cycle.

- Vagally mediated efferent HRV provides an index of the cognitive and emotional resources needed for efficient functioning in challenging environments in which delayed responding and behavioral inhibition are critical.

- Information is encoded in the time between intervals (action potentials, pulsatile release of hormones, etc.). The information contained in the interbeat intervals in the heart’s activity is communicated across multiple systems and helps synchronize the system as a whole.

- Patterns in the activity of cardiovascular afferent neuronal traffic can significantly influence cognitive performance, emotional experience and selfregulatory capacity via inputs to the thalamus, amygdala and other subcortical structures.

- Increased “rate of change” in cardiac sensory neurons (transducing BP, rhythm, etc.) during coherent states increases vagal afferent neuronal traffic, which inhibits thalamic pain pathways at the level of the spinal cord.

- Self-induced positive emotions can shift psychophysiological systems into more globally coherent and harmonious orders that are associated with improved performance and overall well-being.

Physiological Coherence

A state characterized by:

High heart-rhythm coherence (sine-wavelike rhythmic pattern).

Changing DNA Through Intention

The power of intentional thoughts and emotions goes beyond theory at the HeartMath Institute. In a study, researchers have tested this idea and proven its veracity.

HeartMath researchers have gone so far as to show that physical aspects of DNA strands could be influenced by human intention. The article, Modulation of DNA Conformation by Heart-Focused Intention – McCraty, Atkinson, Tomasino, 2003 – describes experiments that achieved such results.

For example, an individual holding three DNA samples was directed to generate heart coherence – a beneficial state of mental, emotional and physical balance and harmony – with the aid of a HeartMath technique that utilizes heart breathing and intentional positive emotions. The individual succeeded, as instructed, to intentionally and simultaniously unwind two of the DNA samples to different extents and leave the third unchanged.

“The results provide experimental evidence to support the hypothesis that aspects of the DNA molecule can be altered through intentionality,” the article states. “The data indicate that when individuals are in a heart-focused, loving state and in a more coherent mode of physiological functioning, they have a greater ability to alter the conformation of DNA.

“Individuals capable of generating high ratios of heart coherence were able to alter DNA conformation according to their intention. … Control group participants showed low ratios of heart coherence and were unable to intentionally alter the conformation of DNA.”

Heart Intelligence, the Unifying Factor

The influence or control individuals can have on their DNA – who and what they are and will become – is further illuminated in HeartMath founder Doc Childre’s theory of heart intelligence. Childre postulates that “an energetic connection or coupling of information” occurs between the DNA in cells and higher dimensional structures – the higher self or spirit.

Childre further postulates, “The heart serves as a key access point through which information originating in the higher dimensional structures is coupled into the physical human system (including DNA), and that states of heart coherence generated through experiencing heartfelt positive emotions increase this coupling.”

The heart, which generates a much stronger electromagnetic field than the brain’s, provides the energetic field that binds together the higher dimensional structures and the body’s many systems as well as its DNA.

Childre’s theory of heart intelligence proposes that “individuals who are able to maintain states of heart coherence have increased coupling to the higher dimensional structures and would thus be more able to produce changes in the DNA.”

Heart-focused self-regulation techniques and assistive technologies that provide real-time HRV coherence feedback provide a systematic process for self-regulating thoughts, emotions, behaviors and increasing physiological coherence.

The first step in most of the techniques developed by the HeartMath Institute is called Heart-Focused Breathing, which includes placing one’s attention in the center of the chest (the area of the heart) and imagining the breath is flowing in and out of the chest area while breathing a little slower and deeper than usual. Conscious regulation of one’s respiration at a 10-second rhythm (five seconds in and five seconds out) (0.1 hertz) increases cardiac coherence and starts the process of shifting into a more coherent state

With conscious control over breathing, an individual can slow the rate and increase the depth of the breathing rhythm. This takes advantage of physiological mechanisms to modulate efferent vagal activity and thus the heart rhythm.

This increases vagal afferent nerve traffic and increases the coherence (stability) in the patterns of vagal afferent nerve traffic. In turn, this influences the neural systems involved in regulating sympathetic outflow, informing emotional experience and synchronizing neural structures underlying cognitive processes.

“We are coming to understand health not as the absence of disease, but rather as the process by which individuals maintain their sense of coherence (i.e. sense that life is comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful) and ability to function in the face of changes in themselves and their relationships with their environment